Those of us who have extensively worked with ASM over the years can attest to its excellence. It has become the standard for storing our databases, whether on commodity hardware or Oracle-engineered systems, and this holds true both on-premises and in the cloud. Over 20 years have passed since its inception, and time has revealed several aspects or capabilities that could be improved. This is the first article in a series of three, where I will begin by explaining why Oracle aimed to create a worthy successor to ASM for Exadata systems.

Areas of Improvement

ASM transitioned from being a standalone installation to an integrated part of the Grid Infrastructure. ASM offered robust performance as it was never an intermediary layer between the database and the disk but rather functioned as an extent map manager. This allowed databases to access storage directly. However, resizing a diskgroup was a complex task. It involved either changing the size of the ASM disks (or griddisks in Exadata platforms) if unused space was available—which was rarely the case—or deleting Asm disks/griddisks from one diskgroup to allocate them to another, triggering a time-consuming rebalance operation.. Thus, daily operations and usage were efficient, except when it came to resizing diskgroup space. This is improvement area number one.

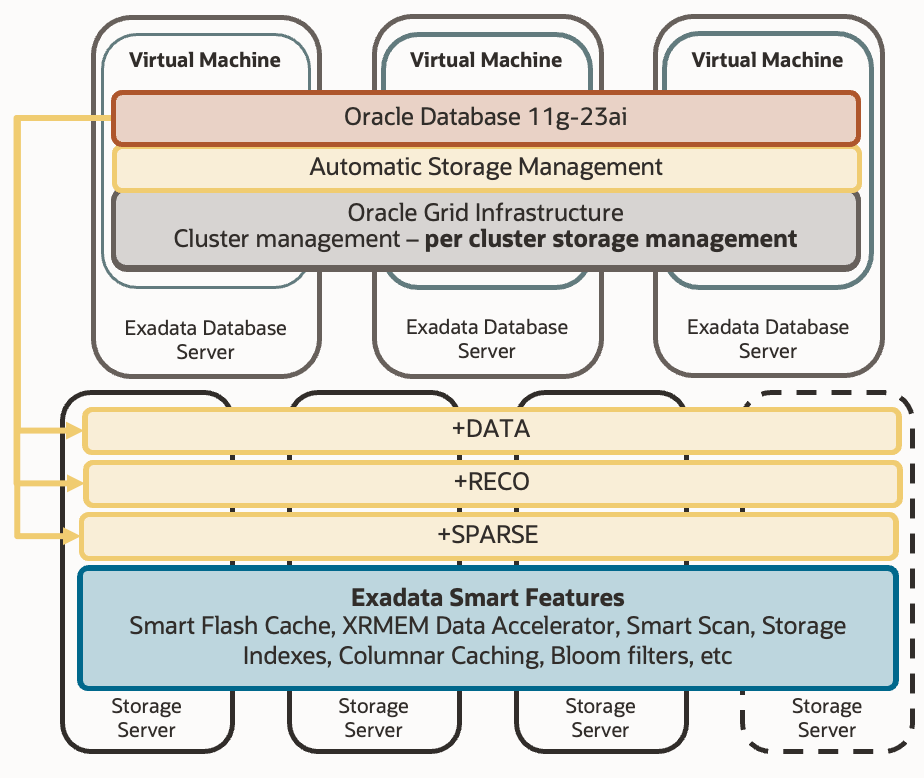

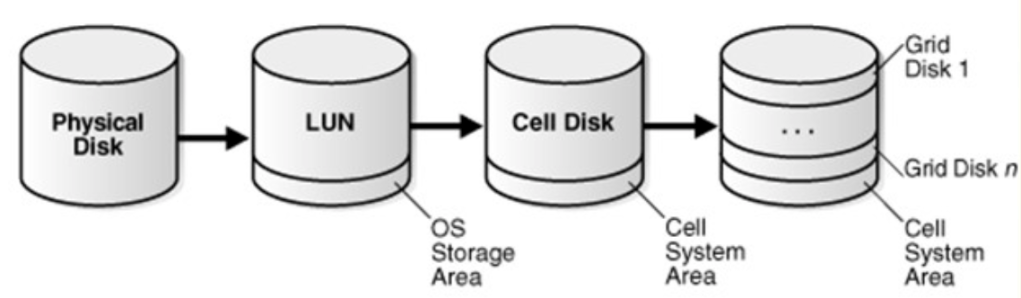

In Exadata systems, ASM constructed celldisks from physical disk partitions and griddisks from celldisks. An ASM diskgroup in Exadata comprised griddisks from different storage cells (actual failgroups). If the Exadata system was virtualized—which is often the case nowadays— creating DATA and RECO diskgroups for each of the virtual clusters became necessary. This meant that space had to be rigidly distributed among different diskgroups (two per Virtual Cluster), segmenting the space. Hence, we faced a compromise decision where we divided the net space of the storage cells among the Virtual Clusters. If we miscalculated or mispredicted the size, we were forced to rebalance space among the diskgroups, or even recreate the VC on cloud platforms. We will call this improvement area number two.

Another weak point of ASM involved thin clones. We’ve discussed this in great detail in several of my previous articles, but in summary, we had two options in Exadata systems: using sparse diskgroups which allowed us to have clones with smart scan and good performance but required maintaining the parent database in read-only mode, or using ACFS which allowed the parent database to be read-write but with degrading performance over time (and without smart scan). Moreover, the parent database had to be located in the same infrastructure/storage that provides thin cloning capability; either in the sparse diskgroup or in ACFS. If we needed to take a thin clone from the production database, which was in “DATA”, we first had to move it or copy it to the SPARSE diskgroup. This destroys many use cases. In other words: with ASM, we couldn’t have a thin clone with A) good performance, B) Exadata SMART SCAN capabilities, and C) a read-write parent situated in its original location. This is our third area for improvement.

Lastly, the issue of redundancy. The standard diskgroup type in ASM allows for external, normal, and high redundancy (0 additional copies of each AU, 1 additional copy per AU, 2 additional copies per AU). But this redundancy applied to all its contents, meaning that files from one database had to have the same redundancy as those from another database, even if one was for production and the other for development. To address this, Oracle introduced Flex diskgroups, which allowed the creation of file groups within a single diskgroup, each with a defined redundancy level. Additionally, you could set a maximum quota per group to ensure that a “rogue” database didn’t consume all the physical space from others in the same diskgroup. This was definitely a step forward, but Flex diskgroups required three failgroups to provide normal redundancy and five failgroups for high redundancy. While the net space occupied didn’t increase, it did raise the requirements for a larger number of failgroups. Moreover, it did not solve the problem of space compartmentalization in virtualized Exadatas; a database in one VC could not access the same diskgroup (flex or otherwise) as a database in a different VC. It was a commendable initial effort that ultimately fell short. It was never enabled in ExaDB-D or ExaC@C services. Redundancy will be our fourth area of improvement for ASM.

Exascale is the software evolution of ASM in Exadata systems, addressing all the previous limitations of space compartmentalization, redundancy, and thin clones with a logical, proprietary, and highly effective solution.

In the next article, I will explain the architecture of Exascale and how this architecture addresses each of these use cases. Later, in a third chapter, we will discuss the new cloud service, based on Exascale software, called “Exadata Database Service on Dedicated Infrastructure” (ExaDB-XS). Enjoy!

2 responses to “Exascale (1/3) – Why ASM Needed an Heir Worthy of the 21st Century”

[…] This is part two of a three-part series on Exascale. If you haven’t read the first part, I recommend checking it out here. […]

LikeLike

[…] This is part three of a three-part series on Exascale. If you haven’t read the articles, I suggest starting out here. […]

LikeLike