One of the fundamental milestones achieved by the Oracle Multitenant architecture (CDBs and PDBs) is the ability to online rebalance resources between databases; CPU, memory, and even IO (throughput or IOPS). For example, with multitenant, we can immediately rebalance free memory from one PDB to another; something that is currently impossible to do between two virtual machines. Thanks to this capability, the more PDBs we consolidate in a single container database (CDB), the more likely we are to find free/unused resources throughout the container. These resources can be used to enhance the activity of active databases.

This is, in Oracle, the term “consolidation” is not tied to the term “isolation”. The consolidation of PDBs into CDBs implies “resource efficiency” and “mobility”, and has caused DBAs to change their work approach and assume this consolidation mindset when thinking about new architectures.

This mindset is more than just an Oracle marketing statement; it is a relevant technical change that has enabled a plethora of improvements, which have subsequently cascaded. One of these improvements is related to the way databases are deployed in an Real Application Cluster (RAC).

RAC Database Deployment

In 19c or earlier RACs, and especially for nonCDB architectures, there were two options to define on which nodes nodes each database instance would start, including its dynamic services:

Admin-managed databases: With this configuration, we nominally define in which RAC nodes our database will have instances and where the dynamic services will be placed. It is an explicit assignment where we directly control which databases and services run on each server, allowing us to distribute the load of different databases among the different nodes of the RAC with a very granular and specific control. Therefore, it is a simple, attractive configuration that provides a lot of certainty to DBAs. And I venture to guess that this is the most widespread config option still nowadays.

On the other hand, it can be a very costly configuration in terms of administration when managing a large number of databases. For example, in a 4-node RAC where we consolidate 50 PDBs, manually defining the load distribution and service distribution for each of them can be really painful.

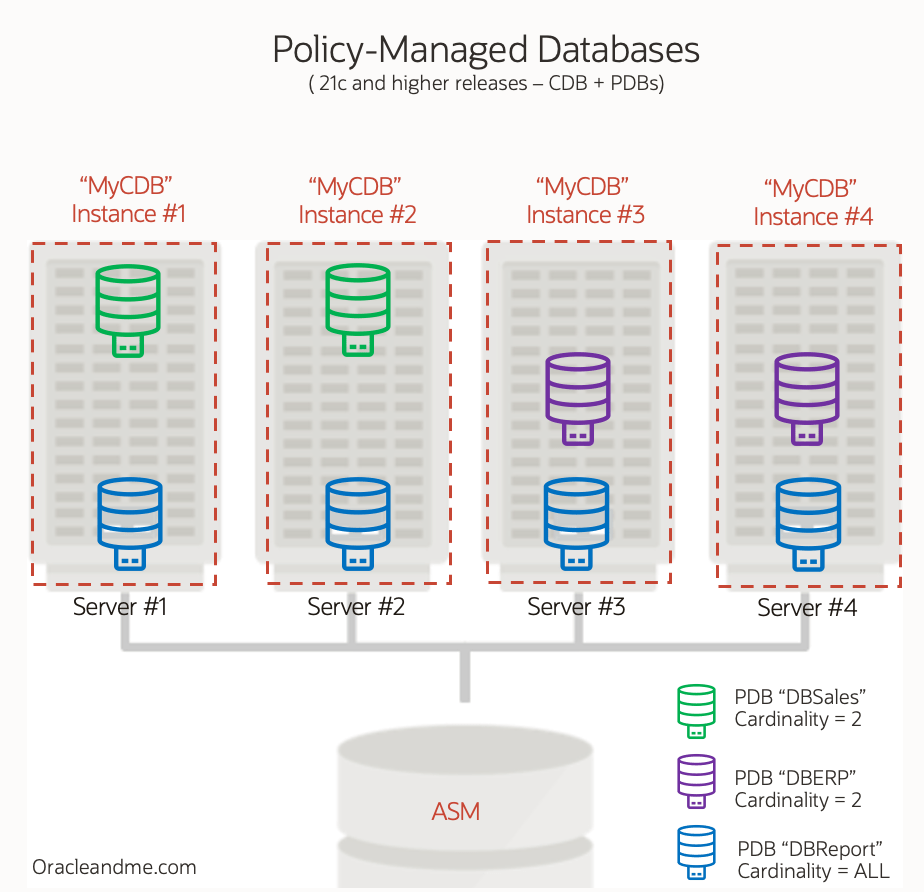

Policy-Managed Databases: In cases where we need to manage a large number of databases in the RAC, the alternative provided by Oracle was the creation of server pools. Each server pool could have a different cardinality (requiring a certain number of RAC nodes). Therefore, a database was associated with a server pool, and Oracle ensured that the database was running on the required number of nodes for that DB in the RAC.

This configuration could be really powerful since, once the cardinality (a number) was set for each of the databases, Oracle takes care for distributing the instances all the time and under any circumstance. Like in the case of a RAC node failure, as the clusterware also would take care of reorganizing the instances to ensure that the minimum level of service quality defined for each of them was met. This could even imply stopping the less important database instances if necessary.

“Policy-Managed Databases” deprecated in 23c

The “Policy-Managed Databases” feature was designed more than 12 years ago, long before the multitenant architecture existed, when the relationship between instance and database was 1 to 1. As an Oracle instance always managed a single database, dealing with the distribution of instances was equivalent to dealing with the distribution of databases.

Today, with our multitenant consolidation mindset, we are specially interested in having Oracle to distribute the PDBs for us along the RAC, not just database instances. In an architecture where each database instance (a CDB$ROOT) is managing multiple PDBs, the minimum granularity unit should now be the PDBs, not instances.

Ideally, in a multitenant RAC, the CDB would start instances on all RAC nodes, and we would define a cardinality and level of importance for each PDB, so that Oracle would take care of distributing each of these 50 PDBs among the different RAC nodes. Depending on the cardinality definition of each PDB, we will have PDBs running on a single node, two nodes, or even on all RAC nodes.

In addition, each PDB would still have its dynamic service definitions, each with its own cardinality definition (limited, of course, to the cardinality of its CDB).

Sounds good, right? Oracle Database 23c implements this new feature, which was introduced in the Innovation Release 21c; the new Policy-Managed Databases :

New Policy-Managed Databases

In 19c, a PDB dynamic service was a clusterware resource, but interestingly, PDBs themselves were not. This meant that the clusterware had no ability to directly manage them. The PDBs were indirectly managed by their dynamic services, which triggered the opening of the PDBs on those nodes where the PDB dynamic service was defined to start.

As we discussed in a previous article, in 23c PDBs are finally a cluster resource. This means that the clusterware has the ability to directly start/stop them on different RAC nodes. And it can even define certain attributes associated with these “PDB” resources to influence this start/stop behaviour.

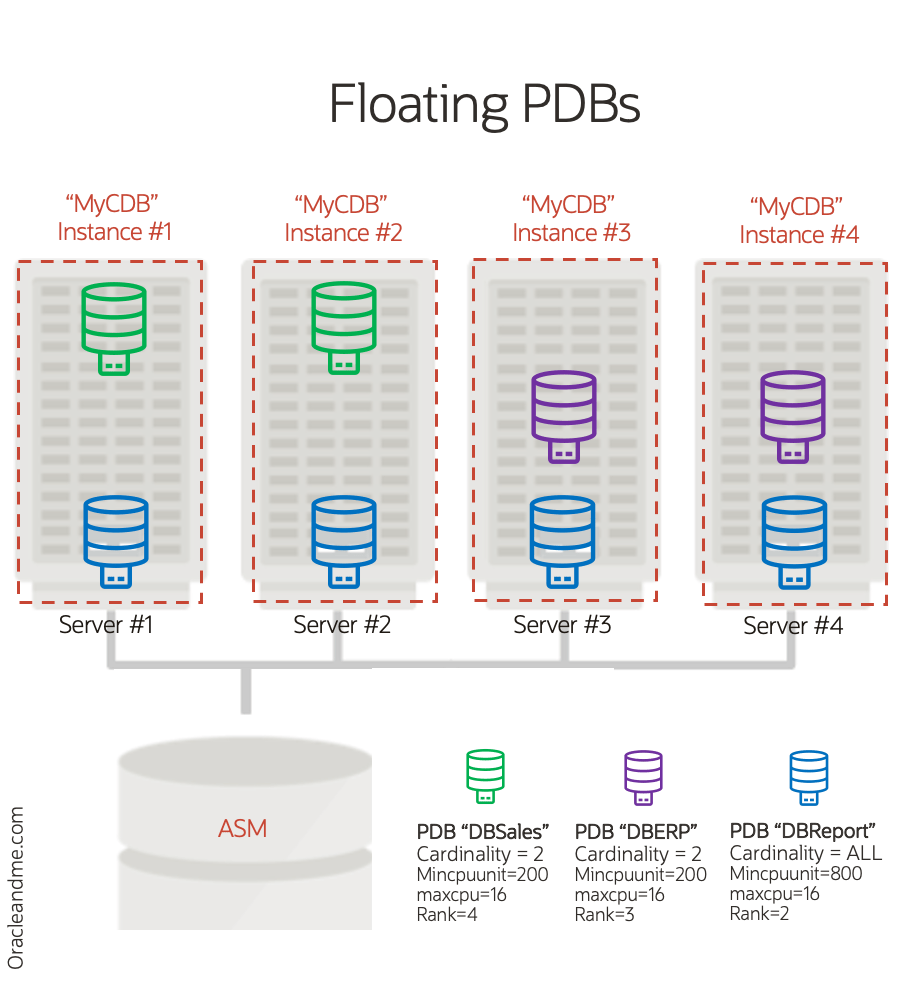

The main attribute, although not the only, that we will define in the “PDB resource” to implement “floating PDBs” is “cardinality”.

“Cardinality” specifies the number of nodes where a PDB should be opened. If the CDB was created in a subset of RAC nodes – naturally still supported, but probably not the ideal approach by default -, the cardinality will apply only to that limited number of CDB instances. If the CDB was created on all the RAC nodes, the PDB cardinality applies to all the DB instances, which equals to all RAC nodes in this case. You can define a number of nodes (1,2) or to ALL, which implies that PDB will try to be started on all the CDB instances. Lets check the syntax:

[oracle@test1 ~]$ srvctl add pdb -d CDB21c_fra145 -pdb PDB1 -cardinality 2Floating PDBs

Perhaps “cardinality” attribute would be sufficient if we never needed to stop any RAC node. In that case, we could define perfect cardinalities for a perfect workload balance across all the RAC nodes, as we would know with absolute certainty the total resources/nodes we expect to have. But this is simply not the case, because a significant portion of routine maintenance is performed online in rolling mode, which involves temporarily stopping one of the RAC nodes at a time. And this means relocating PDBs to honor the cardinality.

In other words, we not only need to define the cardinality of each PDB, but we also need to inform the clusterware of the importance of each PDB and the resources that each of the PDBs requires to keep a minimum performance baseline. In this way, if one of the RAC nodes goes down or is stopped – a situation where we lose a percentage of the whole RAC computing capacity – the clusterware has the ability to prioritize the startup of certain PDBs over others. Or even (if configured in that way), it could stop certain PDBs on a node in order to “receive” other higher priority PDBs after a node shutdown/crash.

So, in addition to the “cardinality” attribute, how can we inform the clusterware of the resources needed by the PDB and its importance? With the “mincpuunit”, “maxcpu”, and “rank” attributes:

“mincpuunit”: The “mincpuunit” parameter in the Clusterware “PDB” resource definition determines the minimum guaranteed amount of CPU for that PDB. This parameter is key to ensuring that a PDB always has sufficient CPU resources to operate efficiently, even during times of high resource demand on the system.

“maxcpu”: This parameter sets the maximum limit of CPU a PDB can use. It is useful for preventing the monopolization of all the free CPU resources pool by a specific PDB, which could negatively impact the performance of other PDBs in the same environment.

[root@test1 ~]# /u01/app/oracle/product/21.0.0.0/dbhome_1/bin/srvctl modify pdb -d CDB21c_fra145 -pdb PDB1 -cardinality 2 -mincpuunit 400 -maxcpu 16“rank”: The higher the rank, the more important the PDB is compared to other databases in the same cluster. The clusterware will firstly start the higher rank PDBs, filling-in it’s required CPUs before assigning CPU for the other PDBs located in the same node. If there are not enough CPU resources in the node, the lower ranked PDBs will not be started (or will be closed in case of a failover).

[root@test1 ~]# /u01/app/oracle/product/21.0.0.0/dbhome_1/bin/srvctl modify pdb -d CDB21c_fra145 -pdb PDB1 -cardinality 2 -mincpuunit 400 -maxcpu 16 -rank 4Once we have properly configured all the parameters, we will finally have the full “Floating PDBs” set-up in place :

Before we wrap up for today; have you noticed another immediate improvement that is obtained when managing load distribution with floating PDBs versus server pools? With which of the two methods do you think the database becomes available again on a surviving node sooner? Indeed, opening or closing a PDB on a different or additional instance is immediate because the instance is already up and running on the other node. There is no need to start a new set of processes and reserve a new chunk of memory in the operating system. In the case of server pools, the movement is not as agile, as in the event of a node’s unavailability, the work is done at the instance level (stopping instances and starting instances if necessary).

Summary

In 23c, we have the opportunity to choose between two ways of deploying PDBs in a RAC:

- “Administrator-Managed deployment“: Same behavior as in past releases. The CDB is created on a specific set of instances (usually all). There is no explicit definition of cardinality in the PDBs. Cardinality is controled with the PDBs dynamic services, defining in which nominal instances they will be running by default (preferred) and to which instances they can failover in case of node unavailability (available).

- The new “Policy-managed deployment” (aka “Floating PDBs”): Don’t be confused by the name. It has nothing to do with traditional server pools. This is the new configuration that allows us to define the cardinality, min/max CPU, and rank for each PDB. The name “policy-managed databases” has been kept because, in fact, with the new canonical Oracle architecture, PDBs are “the” databases.

Great! In the next article, we will have a step-by-step lab on Floating PDBs where we will explore the dynamics of those 4 parameters and delve into the PDBs dynamic services. Stay tuned!